Abstract

Accurate prediction of progression in subjects at risk of Alzheimer’s disease is crucial for enrolling the right subjects in clinical trials. However, a prospective comparison of state-of-the-art algorithms for predicting disease onset and progression is currently lacking. We present the findings of The Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction Of Longitudinal Evolution (TADPOLE) Challenge, which compared the performance of 92 algorithms from 33 international teams at predicting the future trajectory of 219 individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Challenge participants were required to make a prediction, for each month of a 5-year future time period, of three key outcomes: clinical diagnosis, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subdomain (ADAS-Cog13), and total volume of the ventricles. No single submission was best at predicting all three outcomes. For clinical diagnosis and ventricle volume prediction, the best algorithms strongly outperform simple baselines in predictive ability. However, for ADAS-Cog13 no single submitted prediction method was significantly better than random guessing. On a limited, cross-sectional subset of the data emulating clinical trials, performance of best algorithms at predicting clinical diagnosis decreased only slightly (3% error increase) compared to the full longitudinal dataset. Two ensemble methods based on taking the mean and median over all predictions, obtained top scores on almost all tasks. Better than average performance at diagnosis prediction was generally associated with the additional inclusion of features from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). On the other hand, better performance at ventricle volume prediction was associated with inclusion of summary statistics, such as patient-specific biomarker trends. The submission system remains open via the website https://tadpole.grand-challenge.org, while code for submissions is being collated by TADPOLE SHARE: https://tadpole-share.github.io/. Our work suggests that current prediction algorithms are accurate for biomarkers related to clinical diagnosis and ventricle volume, opening up the possibility of cohort refinement in clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease.

1 Introduction

Accurate prediction of the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its longitudinal progression is important for care planning and for patient selection in clinical trials. Current opinion holds that early detection will be critical for the successful administration of disease modifying treatments during presymptomatic phases of the disease prior to widespread brain damage, e.g. when pathological amyloid and tau start to accumulate mehta2017trials . Moreover, accurate prediction of the progression of at-risk subjects will help select homogenous patient groups for clinical trials, thus reducing variability in outcome measures that can obscure positive effects on patients at the right stage to benefit.

Several mathematical and computational methods have been developed to predict the onset and progression of AD. Traditional approaches leverage statistical regression to model relationships between target variables (e.g. clinical diagnosis or cognitive/imaging markers) with other known markers scahill2002mapping ; sabuncu2011dynamics or measures derived from these markers such as the rate of cognitive decline doody2010erratum . More recent approaches involve supervised machine learning techniques such as support vector machines, random forests and artificial neural networks. These approaches have been used to discriminate AD patients from cognitively normal individuals kloppel2008automatic ; zhang2011multimodal , and for discriminating at-risk individuals who convert to AD in a certain time frame from those who do not young2013accurate ; mattila2011disease . The emerging approach of disease progression modelling aims to reconstruct biomarker trajectories or other disease signatures across the disease progression timeline, without relying on clinical diagnoses or estimates of time to symptom onset. Examples include models built on a set of scalar biomarkers to produce discrete fonteijn2012event ; young2014data or continuous jedynak2012computational ; donohue2014estimating ; lorenzi2017probabilistic ; oxtoby2018data ; schiratti2017bayesian biomarker trajectories; spatio-temporal models that focus on evolving image structure bilgel2016multivariate ; marinescu2019dive , potentially conditioned by non-imaging variables koval2018simulating ; and models that emulate putative disease mechanisms to estimate trajectories of change raj2012network ; iturria2016early ; zhou2012predicting . All these models show promise for predicting AD biomarker progression at group and individual levels. However, previous evaluations within individual publications provide limited information because: (1) they use different data sets or subsets of the same dataset, different processing pipelines, and different evaluation metrics and (2) over-training can occur due to heavy use of popular training datasets. Currently, the field lacks a comprehensive comparison of the capabilities of these methods on standardised tasks relevant to real-world applications.

Community challenges have consistently proved effective in moving forward the state of the art in technology to address specific data-analysis problems by providing platforms for unbiased comparative evaluation and incentives to maximise performance on key tasks maier2018rankings . In medical image analysis, for example, such challenges have provided important benchmarks in tasks such as registration murphy2011evaluation and segmentation menze2014multimodal , and revealed fundamental insights about the problem studied, for example in structural brain-connectivity mapping maier2017challenge . Previous challenges in AD include the CADDementia challenge bron2015standardized , which aimed to identify clinical diagnosis from MRI scans. A similar challenge, the International challenge for automated prediction of MCI from MRI data castiglioni2018machine , asked participants to predict diagnosis and conversion status from extracted MRI features of subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study weiner2017recent . Yet another challenge, The Alzheimer’s Disease Big Data DREAM Challenge allen2016crowdsourced , asked participants to predict cognitive decline from genetic and MRI data. These challenges have however several limitations: (i) they did not evaluate the ability of algorithms to predict biomarkers at future timepoints (with the exception of one sub-challenge of DREAM), which is important for patient stratification in clinical trials; (ii) the test data was available to organisers when the competitions were launched, leaving room for potential biases in the design of the challenges; (iii) the training data was drawn from a limited set of modalities.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Prediction Of Longitudinal Evolution (TADPOLE) Challenge (https://tadpole.grand-challenge.org) aims to identify the data, features and approaches that are the most predictive of future progression of subjects at risk of AD. In contrast to previous challenges, our challenge is designed to inform clinical trials through identification of patients most likely to benefit from an effective treatment, i.e., those at early stages of disease who are likely to progress over the short-to-medium term (1-5 years). The challenge focuses on forecasting the trajectories of three key features: clinical status, cognitive decline, and neurodegeneration (brain atrophy), over a five-year timescale. It uses “rollover” subjects from the ADNI study weiner2017recent for whom a history of measurements (imaging, psychology, demographics, genetics) is available, and who are expected to continue in the study, providing future measurements for testing. TADPOLE participants were required to predict future measurements from these individuals and submit their predictions before a given submission deadline. Since the test data did not exist at the time of forecast submissions, the challenge provides a performance comparison substantially less susceptible to many forms of potential bias than previous studies and challenges. The design choices were published marinescu2018tadpole before the test set was acquired and analysed. TADPOLE also goes beyond previous challenges by drawing on a vast set of multimodal measurements from ADNI which might support prediction of AD progression.

This article presents the results of the TADPOLE Challenge and documents its key findings. We summarise the challenge design and present the results of the 92 prediction algorithms contributed by 33 participating teams worldwide, evaluated after an 18-month follow-up period. We discuss the results obtained by TADPOLE participants, which represent the current state-of-the-art in Alzheimer’s disease prediction. To understand what key characteristics of algorithms were important for good predictions, we also report results on which input data features were most informative, and which feature selection strategies, data imputation methods and classes of algorithms were most effective.

2 Results

2.1 Predictions

TADPOLE Challenge asked participants to forecast three key biomarkers: (1) clinical diagnosis, which can be either cognitively normal (CN), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or probable AD; (2) Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale Cognitive Subdomain (ADAS-Cog13) score; and (3) ventricle volume (divided by intra-cranial volume) from MRI. The exact time of future data acquisitions for any given individual was unknown at forecast time, so participants submitted month-by-month predictions for every individual. Predictions of clinical status comprise relative likelihoods of each option (CN, MCI, and AD) for each individual at each month. Predictions of ADAS-Cog13 and ventricle volume comprise a best-guess estimate as well as a 50% confidence interval for each individual at each month. Full details on challenge design are given in the TADPOLE white paper marinescu2018tadpole .

2.2 Algorithms

| Submission | Feature selection | Number of features | Missing data imputation | Diagnosis prediction model | ADAS/Vent. prediction model | Training time | Prediction time (one subject) |

| AlgosForGood | manual | 16+5* | forward-filling | Aalen model | linear regression | 1 min. | 1 sec. |

| Apocalypse | manual | 16 | population average | SVM | linear regression | 40 min. | 3 min. |

| ARAMIS-Pascal | manual | 20 | population average | Aalen model | - | 16 sec. | 0.02 sec. |

| ATRI-Biostat-JMM | automatic | 15 | random forest | random forest | linear mixed effects model | 2 days | 1 sec. |

| ATRI-Biostat-LTJMM | automatic | 15 | random forest | random forest | DPM | 2 days | 1 sec. |

| ATRI-Biostat-MA | automatic | 15 | random forest | random forest | DPM + linear mixed effects model | 2 days | 1 sec. |

| BGU-LSTM | automatic | 67 | none | feed-forward NN | LSTM | 1 day | millisec. |

| BGU-RF/ BGU-RFFIX | automatic | 67+1340* | none | semi-temporal RF | semi-temporal RF | a few min. | millisec. |

| BIGS2 | automatic | all | Iterative Thresholded SVD | RF | linear regression | 2.2 sec. | 0.001 sec. |

| Billabong (all) | manual | 15-16 | linear regression | linear scale | non-parametric SM | 7 hours | 0.13 sec. |

| BORREGOSTECMTY | automatic | 100 + 400* | nearest-neighbour | regression ensemble | ensemble of regression + hazard models | 18 hours | 0.001 sec. |

| BravoLab | automatic | 25 | hot deck | LSTM | LSTM | 1 hour | a few sec. |

| CBIL | manual | 21 | linear interpolation | LSTM | LSTM | 1 hour | one min. |

| Chen-MCW | manual | 9 | none | linear regression | DPM | 4 hours | 1 hour |

| CN2L-NeuralNetwork | automatic | all | forward-filling | RNN | RNN | 24 hours | a few sec. |

| CN2L-RandomForest | manual | 200 | forward-filling | RF | RF | 15 min. | 1 min. |

| CN2L-Average | automatic | all | forward-filling | RNN/RF | RNN/RF | 24 hours | 1 min. |

| CyberBrains | manual | 5 | population average | linear regression | linear regression | 20 sec. | 20 sec. |

| DIKU (all) | semi-automatic | 18 | none | Bayesian classifier/LDA + DPM | DPM | 290 sec. | 0.025 sec. |

| DIVE | manual | 13 | none | KDE+DPM | DPM | 20 min. | 0.06 sec. |

| EMC1 | automatic | 250 | nearest neighbour | DPM + 2D spline + SVM | DPM + 2D spline | 80 min. | a few sec. |

| EMC-EB | automatic | 200-338 | nearest-neighbour | SVM classifier | SVM regressor | 20 sec. | a few sec. |

| FortuneTellerFish-Control | manual | 19 | nearest neighbour | multiclass ECOC SVM | linear mixed effects model | 1 min. | 1 sec. |

| FortuneTellerFish-SuStaIn | manual | 19 | nearest neighbour | multiclass ECOC SVM + DPM | linear mixed effects model + DPM | 5 hours | 1 sec. |

| Frog | automatic | 70+420* | none | gradient boosting | gradient boosting | 1 hour | - |

| GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR | semi-automatic | all | forward-fill/nearest-neigh. | multi-state model | DPM + regression | 15 min. | 2 min. |

| GlassFrog-SM | manual | 7 | linear model | multi-state model | parametric SM | 93 sec. | 0.1 sec. |

| GlassFrog-Average | semi-automatic | all | forward-fill/linear | multi-state model | DPM + SM + regression | 15 min. | 2 min. |

| IBM-OZ-Res | manual | Oct-15 | filled with zero | stochastic gradient boosting | stochastic gradient boosting | 20 min. | 0.1 sec. |

| ITESMCEM | manual | 48 | mean of previous values | RF | LASSO + Bayesian ridge regression | 20 min. | 0.3 sec. |

| lmaUCL (all) | manual | 5 | regression | multi-task learning | multi-task learning | 2 hours | millisec. |

| Mayo-BAI-ASU | manual | 15 | population average | linear mixed effects model | linear mixed effects model | 20 min. | 1.3 sec. |

| Orange | manual | 17 | none | clinician’s decision tree | clinician’s decision tree | none | 0.2 sec. |

| Rocket | manual | 6 | median of diagnostic group | linear mixed effects model | DPM | 5 min. | 0.3 sec. |

| SBIA | manual | 30-70 | dropped visits with missing data | SVM + density estimator | linear mixed effects model | 1 min. | a few sec. |

| SPMC-Plymouth (all) | automatic | 20 | none | unknown | - | unknown | 1 min. |

| SmallHeads-NeuralNetwork | automatic | 376 | nearest neighbour | deep fully -connected NN | deep fully -connected NN | 40 min. | 0.06 sec. |

| SmallHeads-LinMixedEffects | automatic | unknown | nearest neighbour | - | linear mixed effects model | 25 min. | 0.13 sec. |

| Sunshine (all) | semi-automatic | 6 | population average | SVM | linear model | 30 min. | 1 min. |

| Threedays | manual | 16 | none | RF | - | 1 min. | 3 sec. |

| Tohka-Ciszek-SMNSR | manual | 32 | nearest neighbour | - | SMNSR | several hours | a few sec. |

| Tohka-Ciszek-RandomForestLin | manual | 32 | mean patient value | RF | linear model | a few min. | a few sec. |

| VikingAI (all) | manual | 10 | none | DPM + ordered logit model | DPM | 10 hours | 8 sec. |

| BenchmaskLastVisit | None | 3 | none | constant model | constant model | 7 sec. | millisec. |

| BenchmarkMixedEffects | None | 3 | none | Gaussian model | linear mixed effects model | 30 sec. | 0.003 sec. |

| BenchmarkMixedEffects-APOE | None | 4 | none | Gaussian model | linear mixed effects model | 30 sec. | 0.003 sec. |

| BenchmarkSVM | manual | 6 | mean of previous values | SVM | support vector regressor (SVR) | 20 sec. | 0.001 sec. |

We had a total of 33 participating teams, who submitted a total of 58 predictions from the longitudinal prediction set (D2), 34 predictions from the cross-sectional prediction set (D3), and 6 predictions from custom prediction sets (see Online Methods section 5.1 for description of D2/D3 datasets). A total of 8 D2/D3 submissions from 6 teams did not have predictions for all three target variables, so we computed the performance metrics for only the submitted target variables. Another 3 submissions lacked confidence intervals for either ADAS-Cog13 or ventricle volume, which we imputed using default low-width confidence ranges of 2 for ADAS-Cog13 and 0.002 for Ventricles normalised by intracranial volume (ICV).

Table 1 summarises the methods used in the submissions in terms of feature selection, handling of missing data, predictive models for clinical diagnosis and ADAS/Ventricles biomarkers, as well as training and prediction times. A detailed description of each method is in Online Methods Section 5.4. In particular, some entries constructed augmented features (i.e. summary statistics), which are extra features such as slope, min/max or moments that are derived from existing features.

In addition to the forecasts submitted by participants, we also evaluated four benchmark methods, which were made available to participants during the submission phase of the challenge: (i) BenchmaskLastVisit uses the measurement of each target from the last available clinical visit as the forecast, (ii) BenchmarkMixedEffects uses a mixed effects model with age as predictor variable for ADAS and Ventricle predictions, and Gaussian likelihood model for diagnosis prediction, (iii) BenchmarkMixedEffectsAPOE is as (ii) but adds APOE status as a covariate and (iv) BenchmarkSVM uses an out-of-the-box support vector machine (SVM) classifier and regressor (SVR) to provide forecasts. More details on these methods can be found in Online Methods section 5.4. We also evaluated two ensemble methods based on taking the mean (ConsensusMean) and median (ConsensusMedian) of the forecasted variables over all submissions.

To control for potentially spurious strong performance arising from multiple comparisons, we also evaluated 100 random predictions by adding Gaussian noise to the forecasts of the simplest benchmark model (BenchmarkLastVisit). In the subsequent results tables we will show, for each performance metric, only the best score obtained by any of these 100 random predictions (RandomisedBest) – See end of Online Methods section 5.4 for more information on RandomisedBest.

2.3 Forecasts from the longitudinal prediction set (D2)

| Overall | Diagnosis | ADAS-Cog13 | Ventricles (% ICV) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submission | Rank | Rank | MAUC | BCA | Rank | MAE | WES | CPA | Rank | MAE | WES | CPA |

| ConsensusMedian | - | - | 0.925 | 0.857 | - | 5.12 | 5.01 | 0.28 | - | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.09 |

| Frog | 1 | 1 | 0.931 | 0.849 | 4 | 4.85 | 4.74 | 0.44 | 10 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| ConsensusMean | - | - | 0.920 | 0.835 | - | 3.75 | 3.54 | 0.00 | - | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.13 |

| EMC1-Std | 2 | 8 | 0.898 | 0.811 | 23-24 | 6.05 | 5.40 | 0.45 | 1-2 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.43 |

| VikingAI-Sigmoid | 3 | 16 | 0.875 | 0.760 | 7 | 5.20 | 5.11 | 0.02 | 11-12 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.20 |

| EMC1-Custom | 4 | 11 | 0.892 | 0.798 | 23-24 | 6.05 | 5.40 | 0.45 | 1-2 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 0.43 |

| CBIL | 5 | 9 | 0.897 | 0.803 | 15 | 5.66 | 5.65 | 0.37 | 13 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| Apocalypse | 6 | 7 | 0.902 | 0.827 | 14 | 5.57 | 5.57 | 0.50 | 20 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| GlassFrog-Average | 7 | 4-6 | 0.902 | 0.825 | 8 | 5.26 | 5.27 | 0.26 | 29 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.33 |

| GlassFrog-SM | 8 | 4-6 | 0.902 | 0.825 | 17 | 5.77 | 5.92 | 0.20 | 21 | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.20 |

| BORREGOTECMTY | 9 | 19 | 0.866 | 0.808 | 20 | 5.90 | 5.82 | 0.39 | 5 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| BenchmarkMixedEffects | - | - | 0.846 | 0.706 | - | 4.19 | 4.19 | 0.31 | - | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.50 |

| EMC-EB | 10 | 3 | 0.907 | 0.805 | 39 | 6.75 | 6.66 | 0.50 | 9 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.48 |

| lmaUCL-Covariates | 11-12 | 22 | 0.852 | 0.760 | 27 | 6.28 | 6.29 | 0.28 | 3 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| CN2L-Average | 11-12 | 27 | 0.843 | 0.792 | 9 | 5.31 | 5.31 | 0.35 | 16 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.33 |

| VikingAI-Logistic | 13 | 20 | 0.865 | 0.754 | 21 | 6.02 | 5.91 | 0.26 | 11-12 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.20 |

| lmaUCL-Std | 14 | 21 | 0.859 | 0.781 | 28 | 6.30 | 6.33 | 0.26 | 4 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.09 |

| RandomisedBest | - | - | 0.800 | 0.803 | - | 4.52 | 4.52 | 0.27 | - | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.33 |

| CN2L-RandomForest | 15-16 | 10 | 0.896 | 0.792 | 16 | 5.73 | 5.73 | 0.42 | 31 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.41 |

| FortuneTellerFish-SuStaIn | 15-16 | 40 | 0.806 | 0.685 | 3 | 4.81 | 4.81 | 0.21 | 14 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.18 |

| CN2L-NeuralNetwork | 17 | 41 | 0.783 | 0.717 | 10 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 0.34 | 7 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.27 |

| BenchmarkMixedEffectsAPOE | 18 | 35 | 0.822 | 0.749 | 2 | 4.75 | 4.75 | 0.36 | 23 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.40 |

| Tohka-Ciszek-RandomForestLin | 19 | 17 | 0.875 | 0.796 | 22 | 6.03 | 6.03 | 0.15 | 22 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.37 |

| BGU-LSTM | 20 | 12 | 0.883 | 0.779 | 25 | 6.09 | 6.12 | 0.39 | 25 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.23 |

| DIKU-GeneralisedLog-Custom | 21 | 13 | 0.878 | 0.790 | 11-12 | 5.40 | 5.40 | 0.26 | 38-39 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.05 |

| DIKU-GeneralisedLog-Std | 22 | 14 | 0.877 | 0.790 | 11-12 | 5.40 | 5.40 | 0.26 | 38-39 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.05 |

| CyberBrains | 23 | 34 | 0.823 | 0.747 | 6 | 5.16 | 5.16 | 0.24 | 26 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.12 |

| AlgosForGood | 24 | 24 | 0.847 | 0.810 | 13 | 5.46 | 5.11 | 0.13 | 30 | 0.69 | 3.31 | 0.19 |

| lmaUCL-halfD1 | 25 | 26 | 0.845 | 0.753 | 38 | 6.53 | 6.51 | 0.31 | 6 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.13 |

| BGU-RF | 26 | 28 | 0.838 | 0.673 | 29-30 | 6.33 | 6.10 | 0.35 | 17-18 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.26 |

| Mayo-BAI-ASU | 27 | 52 | 0.691 | 0.624 | 5 | 4.98 | 4.98 | 0.32 | 19 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.40 |

| BGU-RFFIX | 28 | 32 | 0.831 | 0.673 | 29-30 | 6.33 | 6.10 | 0.35 | 17-18 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.26 |

| FortuneTellerFish-Control | 29 | 31 | 0.834 | 0.692 | 1 | 4.70 | 4.70 | 0.22 | 50 | 1.38 | 1.38 | 0.50 |

| GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR | 30 | 4-6 | 0.902 | 0.825 | 31 | 6.34 | 6.21 | 0.47 | 51 | 1.66 | 1.59 | 0.41 |

| SBIA | 31 | 43 | 0.776 | 0.721 | 43 | 7.10 | 7.38 | 0.40 | 8 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.13 |

| Chen-MCW-Stratify | 32 | 23 | 0.848 | 0.783 | 36-37 | 6.48 | 6.24 | 0.23 | 36-37 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.11 |

| Rocket | 33 | 54 | 0.680 | 0.519 | 18 | 5.81 | 5.71 | 0.34 | 28 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.29 |

| BenchmarkSVM | 34-35 | 30 | 0.836 | 0.764 | 40 | 6.82 | 6.82 | 0.42 | 32 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.50 |

| Chen-MCW-Std | 34-35 | 29 | 0.836 | 0.778 | 36-37 | 6.48 | 6.24 | 0.23 | 36-37 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.11 |

| DIKU-ModifiedMri-Custom | 36 | 36-37 | 0.807 | 0.670 | 32-35 | 6.44 | 6.44 | 0.27 | 34-35 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| DIKU-ModifiedMri-Std | 37 | 38-39 | 0.806 | 0.670 | 32-35 | 6.44 | 6.44 | 0.27 | 34-35 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.01 |

| DIVE | 38 | 51 | 0.708 | 0.568 | 42 | 7.10 | 7.10 | 0.34 | 15 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.13 |

| ITESMCEM | 39 | 53 | 0.680 | 0.657 | 26 | 6.26 | 6.26 | 0.35 | 33 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.43 |

| BenchmarkLastVisit | 40 | 44-45 | 0.774 | 0.792 | 41 | 7.05 | 7.05 | 0.45 | 27 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.47 |

| Sunshine-Conservative | 41 | 25 | 0.845 | 0.816 | 44-45 | 7.90 | 7.90 | 0.50 | 43-44 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.50 |

| BravoLab | 42 | 46 | 0.771 | 0.682 | 47 | 8.22 | 8.22 | 0.49 | 24 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.41 |

| DIKU-ModifiedLog-Custom | 43 | 36-37 | 0.807 | 0.670 | 32-35 | 6.44 | 6.44 | 0.27 | 47-48 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 0.06 |

| DIKU-ModifiedLog-Std | 44 | 38-39 | 0.806 | 0.670 | 32-35 | 6.44 | 6.44 | 0.27 | 47-48 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 0.06 |

| Sunshine-Std | 45 | 33 | 0.825 | 0.771 | 44-45 | 7.90 | 7.90 | 0.50 | 43-44 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.50 |

| Billabong-UniAV45 | 46 | 49 | 0.720 | 0.616 | 48-49 | 9.22 | 8.82 | 0.29 | 41-42 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 0.45 |

| Billabong-Uni | 47 | 50 | 0.718 | 0.622 | 48-49 | 9.22 | 8.82 | 0.29 | 41-42 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 0.45 |

| ATRI-Biostat-JMM | 48 | 42 | 0.779 | 0.710 | 51 | 12.88 | 69.62 | 0.35 | 54 | 1.95 | 5.12 | 0.33 |

| Billabong-Multi | 49 | 56 | 0.541 | 0.556 | 55 | 27.01 | 19.90 | 0.46 | 40 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.45 |

| ATRI-Biostat-MA | 50 | 47 | 0.741 | 0.671 | 52 | 12.88 | 11.32 | 0.19 | 53 | 1.84 | 5.27 | 0.23 |

| BIGS2 | 51 | 58 | 0.455 | 0.488 | 50 | 11.62 | 14.65 | 0.50 | 49 | 1.20 | 1.12 | 0.07 |

| Billabong-MultiAV45 | 52 | 57 | 0.527 | 0.530 | 56 | 28.45 | 21.22 | 0.47 | 45 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 0.47 |

| ATRI-Biostat-LTJMM | 53 | 55 | 0.636 | 0.563 | 54 | 16.07 | 74.65 | 0.33 | 52 | 1.80 | 5.01 | 0.26 |

| Threedays | - | 2 | 0.921 | 0.823 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ARAMIS-Pascal | - | 15 | 0.876 | 0.850 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IBM-OZ-Res | - | 18 | 0.868 | 0.766 | - | - | - | - | 46 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.50 |

| Orange | - | 44-45 | 0.774 | 0.792 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SMALLHEADS-NeuralNet | - | 48 | 0.737 | 0.605 | 53 | 13.87 | 13.87 | 0.41 | - | - | - | - |

| SMALLHEADS-LinMixedEffects | - | - | - | - | 46 | 8.09 | 7.94 | 0.04 | - | - | - | - |

| Tohka-Ciszek-SMNSR | - | - | - | - | 19 | 5.87 | 5.87 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - |

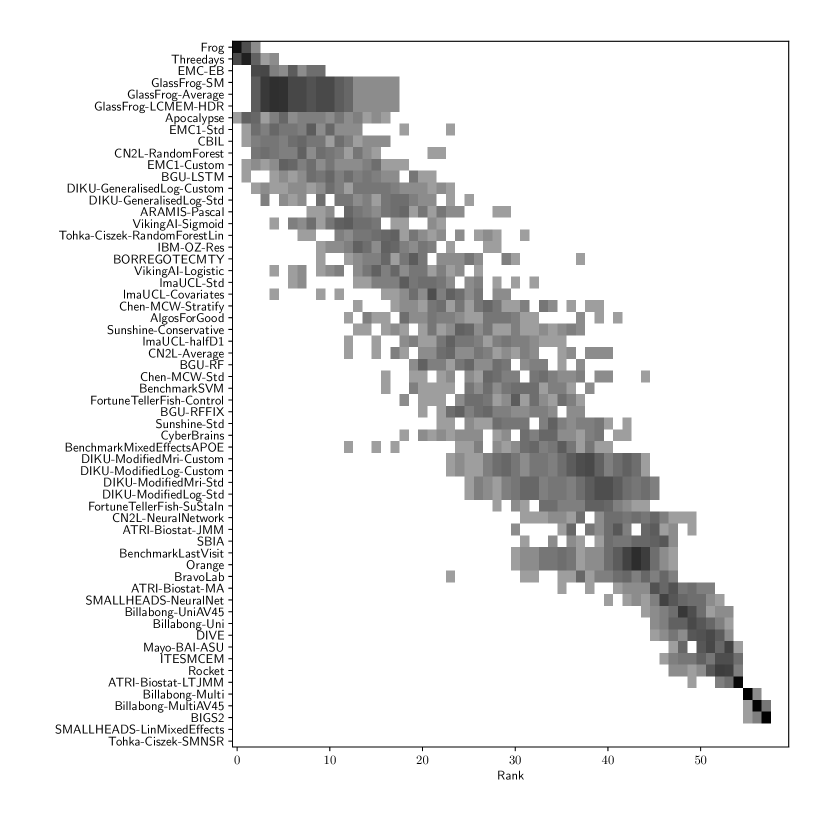

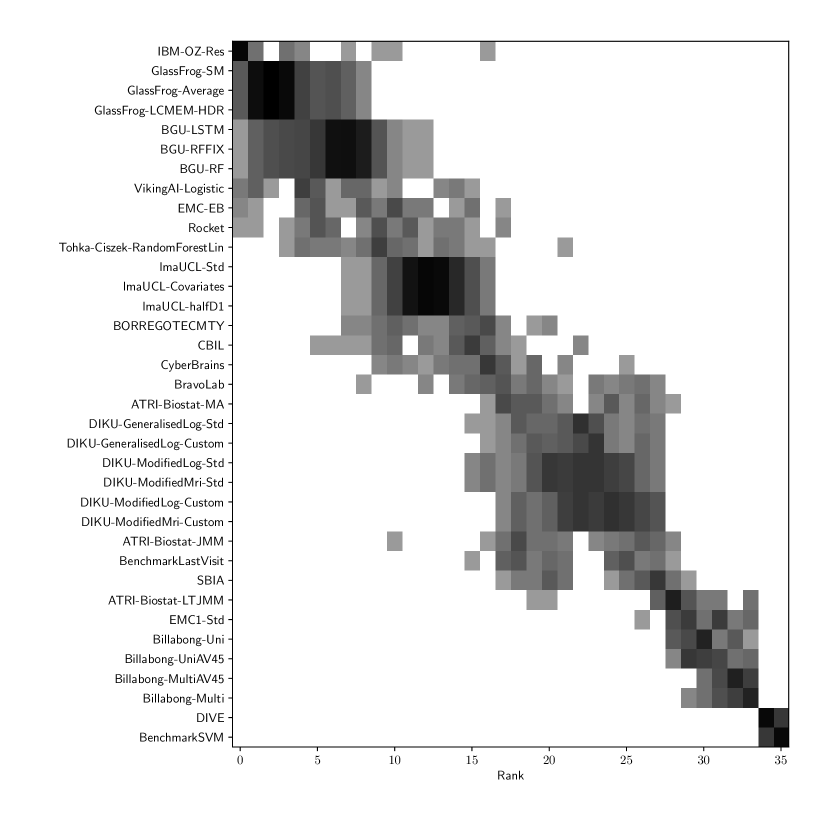

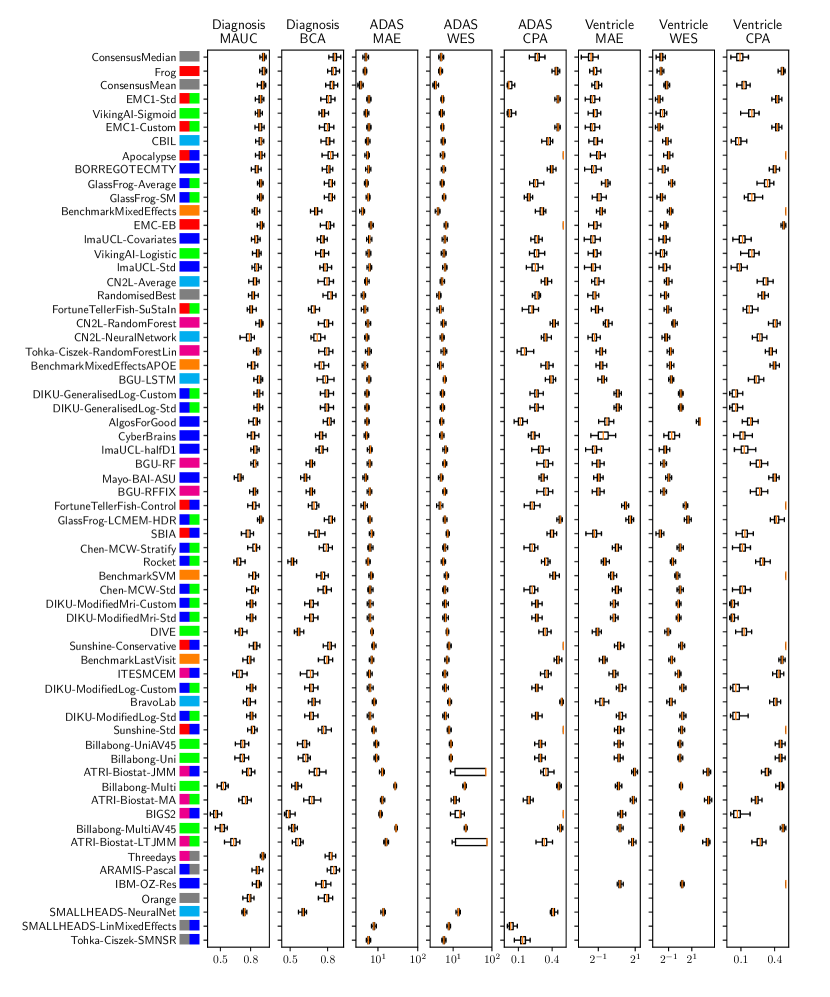

Table 2 compiles all metrics for all TADPOLE submitted forecasts, as well as benchmarks and ensemble forecasts, from the longitudinal D2 prediction set. For details on datasets D2 and D3, see Online Methods section 5.1, while for details on performance metrics see Online Methods section 5.2. Box-plots showing the distribution of scores, computed on 50 bootstraps of the test set, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, while the distribution of ranks is shown in Supplementary Figs. 9 – 11. Among the benchmark methods, BenchmarkMixedEffectsAPOE had the best overall rank of 18, obtaining rank 35 on clinical diagnosis prediction, rank 2 on ADAS-Cog13 and rank 23 on Ventricle volume prediction. Removing the APOE status as covariate proved to significantly increase the predictive performance (BenchmarkMixedEffects), although we do not show ranks for this entry as it was found during the evaluation phase. Among participant methods, the submission with the best overall rank was Frog, obtaining rank 1 for prediction of clinical diagnosis, rank 4 for ADAS-Cog13 and rank 10 for Ventricle volume prediction.

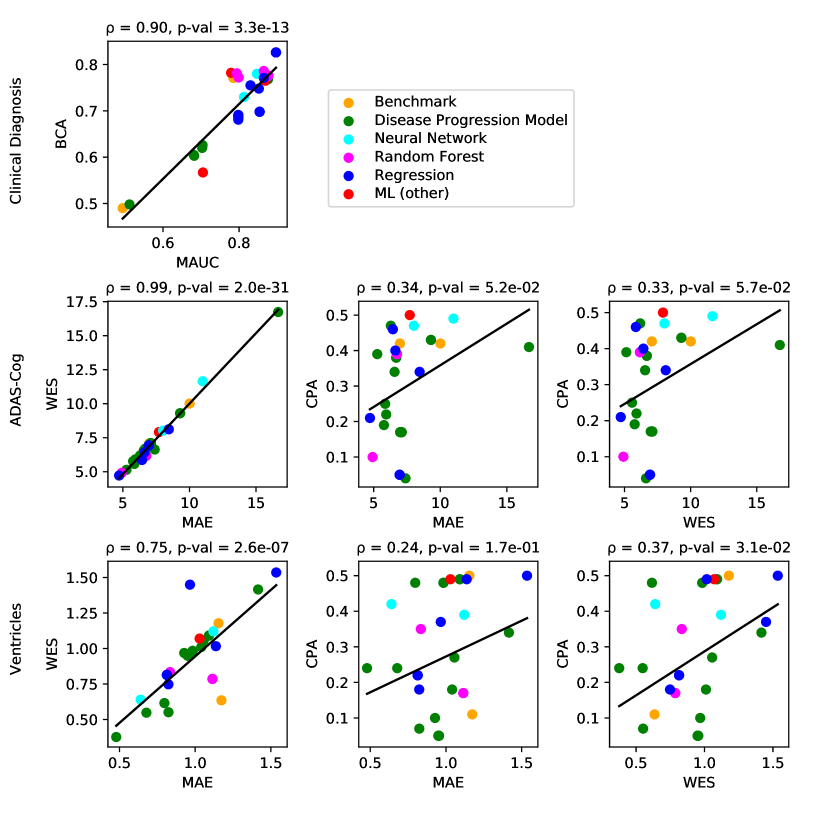

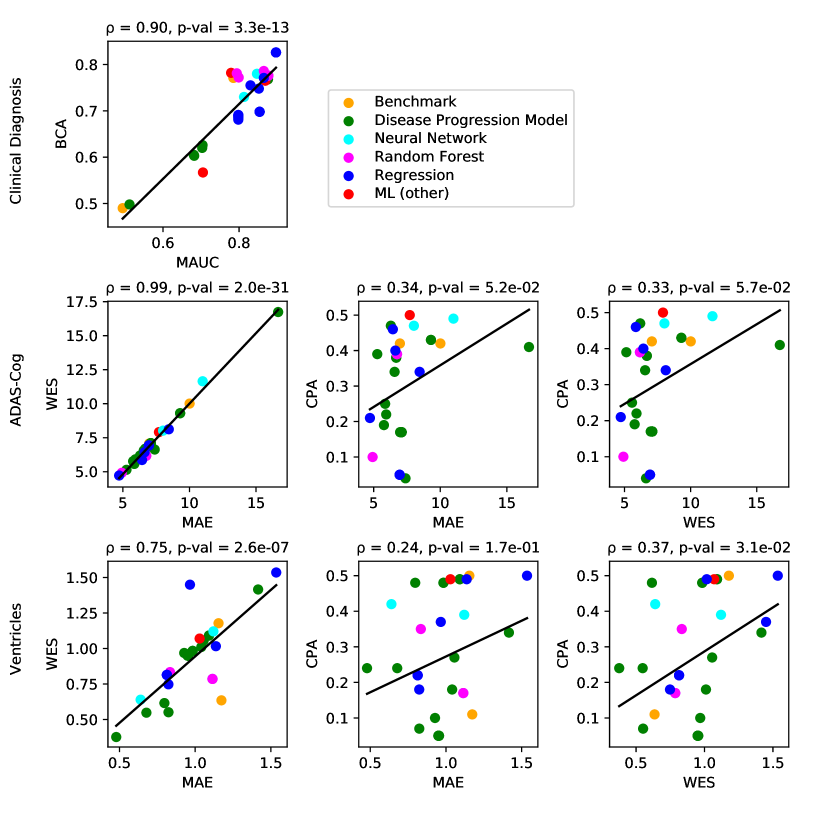

For clinical diagnosis, the best submitted forecasts (team Frog) scored better than all benchmark methods, reducing the error of the best benchmark methods by 58% for the multiclass area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (MAUC) and by 38% for balanced classification accuracy (BCA). Here, the best benchmarks obtained a MAUC of 0.846 (BenchmarkMixedEffects) and a BCA of 0.792 (BenchmarkLastVisit). Among participant methods, Frog had the best MAUC score of 0.931, significantly better than all entries other than Threedays according to the bootstrap test (p-value = 0.24, see Supplementary section B.1 for details on significance testing). Supplementary Figure 9 further shows the variability in performance ranking over bootstrap samples and highlights that the top two entries consistently remain at the top of the ranking. In terms of BCA, ARAMIS-Pascal had the best score of 0.850. Moreover, ensemble methods (ConsensusMedian) achieved the second best MAUC score of 0.925 and the best BCA score of 0.857. In contrast, the best randomised prediction (RandomisedBest) achieved a much lower MAUC of 0.800 and a BCA of 0.803, suggesting entries below these scores did not perform significantly better than random guessing according to the bootstrap test (p-value = 0.01). MAUC and BCA performance metrics had a relatively high correlation across all submissions ( = 0.88, Supplementary Fig. 4).

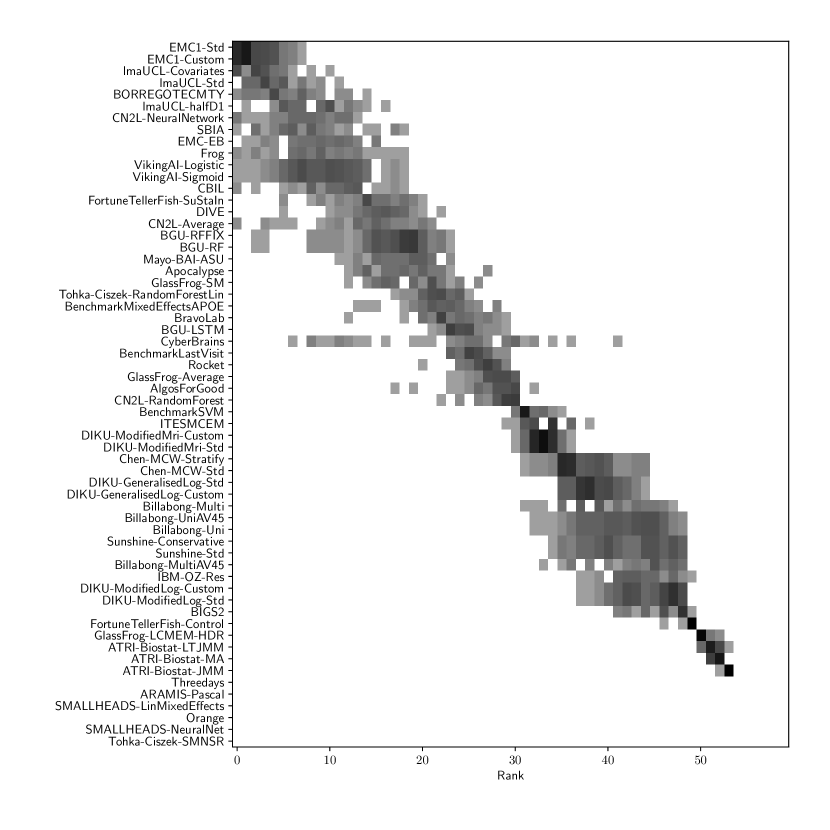

For Ventricle volume, the best submitted forecasts among participants (team EMC1) also scored considerably better than all benchmark methods, reducing the error of the best benchmark methods by almost one third (29%) for mean absolute error (MAE) and around one half (51%) for weighted error score (WES). Here, the best benchmark method (BenchmarkMixedEffects) had an overall Ventricle MAE and WES of 0.56. Among participant submissions, EMC1-Std/-Custom had the best MAE of 0.41 (% ICV), significantly lower than all entries other than lmaUCL-Covariates/-Std/-half-D1, BORREGOTECMTY and SBIA according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (see Supplementary section B.2) – this is also confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 11 by the variability in performance ranking over bootstrap samples. Team EMC1 also had the best Ventricle WES of 0.29, while DIKU-ModifiedMri-Custom/-Std had the best Ventricle coverage probability accuracy (CPA) of 0.01. Ensemble methods (ConsensusMean) achieved the best Ventricle MAE of 0.38. In contrast, the best randomised prediction (RandomisedBest) achieved a higher MAE of 0.46, WES of 0.45 and CPA of 0.33. MAE and WES scores showed high correlation ( = 0.99, Supplementary Fig. 4) and were often of equal value for many submissions (), as teams set equal weights for all subjects analysed. CPA did not correlate (, Supplementary Fig. 4) with either MAE or WES.

For ADAS-Cog13, the best submitted forecasts did not score significantly better than the simple benchmarks. Here, the simple BenchmarkMixedEffects model obtained the second-best MAE of 4.19, which was significantly lower than all other submitted entries according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. BenchmarkMixedEffects also had the best ADAS-Cog13 WES of 4.19, while VikingAI-Sigmoid had the best ADAS-Cog13 CPA of 0.02. Among participants’ submissions, FortuneTellerFish-Control ranked first in ADAS-Cog13 prediction with a MAE of 4.70, which is 11% higher than the error of the best benchmark. Moreover, all participants’ forecasts scored worse than the best randomised prediction (RandomisedBest), which here achieved a MAE of 4.52 and WES of 4.52. Nevertheless, the ensemble method ConsensusMean obtained the best ADAS scores for MAE (3.75), WES (3.54) and CPA (0.0), which along with BenchmarkMixedEffects were the only entries that performed significantly better than random guessing (p-value = 0.01). The MAE and WES scores for ADAS-Cog13 had relatively high correlation (, Supplementary Fig. 4) and were often of equal value for many submissions (). CPA had a weak but significant correlation with MAE (, p-value 0.02) and WES (, p-value 0.02).

2.4 Forecasts from the cross-sectional prediction set (D3) and custom prediction sets

| Overall | Diagnosis | ADAS-Cog13 | Ventricles (% ICV) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submission | Rank | Rank | MAUC | BCA | Rank | MAE | WES | CPA | Rank | MAE | WES | CPA |

| ConsensusMean | - | - | 0.917 | 0.821 | - | 4.58 | 4.34 | 0.12 | - | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.09 |

| ConsensusMedian | - | - | 0.905 | 0.817 | - | 5.44 | 5.37 | 0.19 | - | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.10 |

| GlassFrog-Average | 1 | 2-4 | 0.897 | 0.826 | 5 | 5.86 | 5.57 | 0.25 | 3 | 0.68 | 0.55 | 0.24 |

| GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR | 2 | 2-4 | 0.897 | 0.826 | 9 | 6.57 | 6.56 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.24 |

| GlassFrog-SM | 3 | 2-4 | 0.897 | 0.826 | 4 | 5.77 | 5.77 | 0.19 | 9 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.07 |

| Tohka-Ciszek-RandomForestLin | 4 | 11 | 0.865 | 0.786 | 2 | 4.92 | 4.92 | 0.10 | 10 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.35 |

| RandomisedBest | - | - | 0.811 | 0.783 | - | 4.54 | 4.50 | 0.26 | - | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| lmaUCL-Std | 5-9 | 12-14 | 0.854 | 0.698 | 16-18 | 6.95 | 6.93 | 0.05 | 5-7 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.22 |

| lmaUCL-Covariates | 5-9 | 12-14 | 0.854 | 0.698 | 16-18 | 6.95 | 6.93 | 0.05 | 5-7 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.22 |

| lmaUCL-halfD1 | 5-9 | 12-14 | 0.854 | 0.698 | 16-18 | 6.95 | 6.93 | 0.05 | 5-7 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.22 |

| Rocket | 5-9 | 10 | 0.865 | 0.771 | 3 | 5.27 | 5.14 | 0.39 | 23 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 0.27 |

| VikingAI-Logistic | 5-9 | 8 | 0.876 | 0.768 | 6 | 5.94 | 5.91 | 0.22 | 22 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.18 |

| EMC1-Std | 10 | 30 | 0.705 | 0.567 | 7 | 6.29 | 6.19 | 0.47 | 4 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.48 |

| BenchmarkMixedEffects | - | - | 0.839 | 0.728 | - | 4.23 | 4.23 | 0.34 | - | 1.13 | 1.13 | 0.50 |

| SBIA | 11 | 28 | 0.779 | 0.782 | 10 | 6.63 | 6.43 | 0.40 | 8 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.18 |

| BGU-LSTM | 12-14 | 5-7 | 0.877 | 0.776 | 13-15 | 6.75 | 6.17 | 0.39 | 26-28 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 0.17 |

| BGU-RFFIX | 12-14 | 5-7 | 0.877 | 0.776 | 13-15 | 6.75 | 6.17 | 0.39 | 26-28 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 0.17 |

| BGU-RF | 12-14 | 5-7 | 0.877 | 0.776 | 13-15 | 6.75 | 6.17 | 0.39 | 26-28 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 0.17 |

| BravoLab | 15 | 18 | 0.813 | 0.730 | 28 | 8.02 | 8.02 | 0.47 | 2 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.42 |

| BORREGOTECMTY | 16-17 | 15 | 0.852 | 0.748 | 8 | 6.44 | 5.86 | 0.46 | 30 | 1.14 | 1.02 | 0.49 |

| CyberBrains | 16-17 | 17 | 0.830 | 0.755 | 1 | 4.72 | 4.72 | 0.21 | 35 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 0.50 |

| ATRI-Biostat-MA | 18 | 19 | 0.799 | 0.772 | 26 | 7.39 | 6.63 | 0.04 | 11 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.10 |

| DIKU-GeneralisedLog-Std | 19-20 | 20 | 0.798 | 0.684 | 20-21 | 6.99 | 6.99 | 0.17 | 16-17 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| EMC-EB | 19-20 | 9 | 0.869 | 0.765 | 27 | 7.71 | 7.91 | 0.50 | 21 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.49 |

| DIKU-GeneralisedLog-Custom | 21 | 21 | 0.798 | 0.681 | 20-21 | 6.99 | 6.99 | 0.17 | 16-17 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| DIKU-ModifiedLog-Std | 22-23 | 22-23 | 0.798 | 0.688 | 22-25 | 7.10 | 7.10 | 0.17 | 12-15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| DIKU-ModifiedMri-Std | 22-23 | 22-23 | 0.798 | 0.688 | 22-25 | 7.10 | 7.10 | 0.17 | 12-15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| DIKU-ModifiedMri-Custom | 24-25 | 24-25 | 0.798 | 0.691 | 22-25 | 7.10 | 7.10 | 0.17 | 12-15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| DIKU-ModifiedLog-Custom | 24-25 | 24-25 | 0.798 | 0.691 | 22-25 | 7.10 | 7.10 | 0.17 | 12-15 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 |

| Billabong-Uni | 26 | 31 | 0.704 | 0.626 | 11-12 | 6.69 | 6.69 | 0.38 | 19-20 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.48 |

| Billabong-UniAV45 | 27 | 32 | 0.703 | 0.620 | 11-12 | 6.69 | 6.69 | 0.38 | 19-20 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.48 |

| ATRI-Biostat-JMM | 28 | 26 | 0.794 | 0.781 | 29 | 8.45 | 8.12 | 0.34 | 18 | 0.97 | 1.45 | 0.37 |

| CBIL | 29 | 16 | 0.847 | 0.780 | 33 | 10.99 | 11.65 | 0.49 | 29 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.39 |

| BenchmarkLastVisit | 30 | 27 | 0.785 | 0.771 | 19 | 6.97 | 7.07 | 0.42 | 33 | 1.17 | 0.64 | 0.11 |

| Billabong-MultiAV45 | 31 | 33 | 0.682 | 0.603 | 30-31 | 9.30 | 9.30 | 0.43 | 24-25 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.49 |

| Billabong-Multi | 32 | 34 | 0.681 | 0.605 | 30-31 | 9.30 | 9.30 | 0.43 | 24-25 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.49 |

| ATRI-Biostat-LTJMM | 33 | 29 | 0.732 | 0.675 | 34 | 12.74 | 63.98 | 0.37 | 32 | 1.17 | 1.07 | 0.40 |

| BenchmarkSVM | 34 | 36 | 0.494 | 0.490 | 32 | 10.01 | 10.01 | 0.42 | 31 | 1.15 | 1.18 | 0.50 |

| DIVE | 35 | 35 | 0.512 | 0.498 | 35 | 16.66 | 16.74 | 0.41 | 34 | 1.42 | 1.42 | 0.34 |

| IBM-OZ-Res | - | 1 | 0.905 | 0.830 | - | - | - | - | 36 | 1.77 | 1.77 | 0.50 |

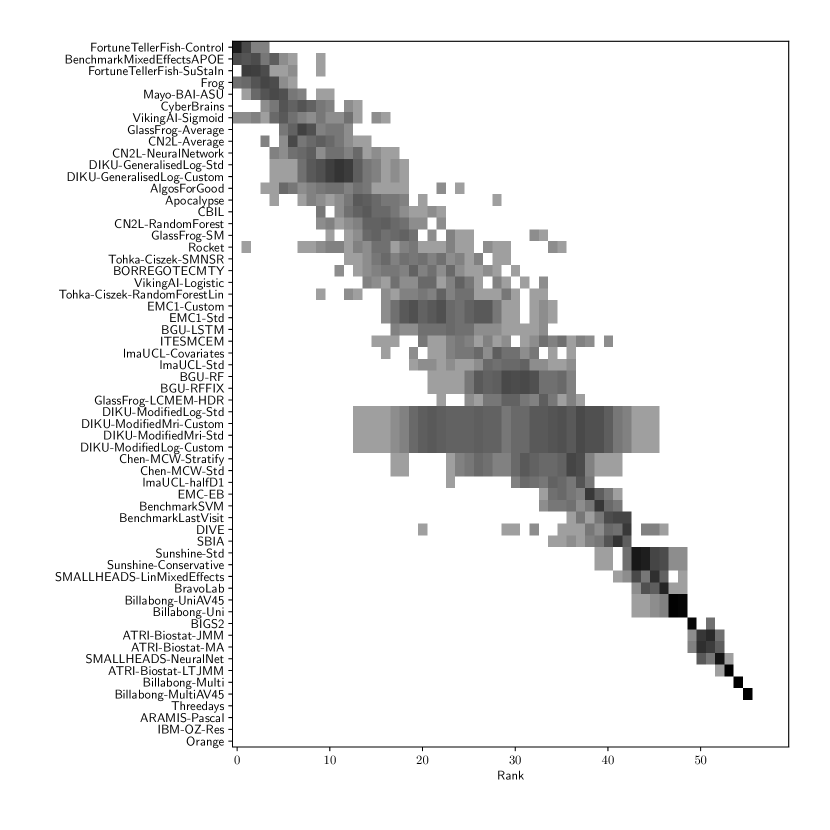

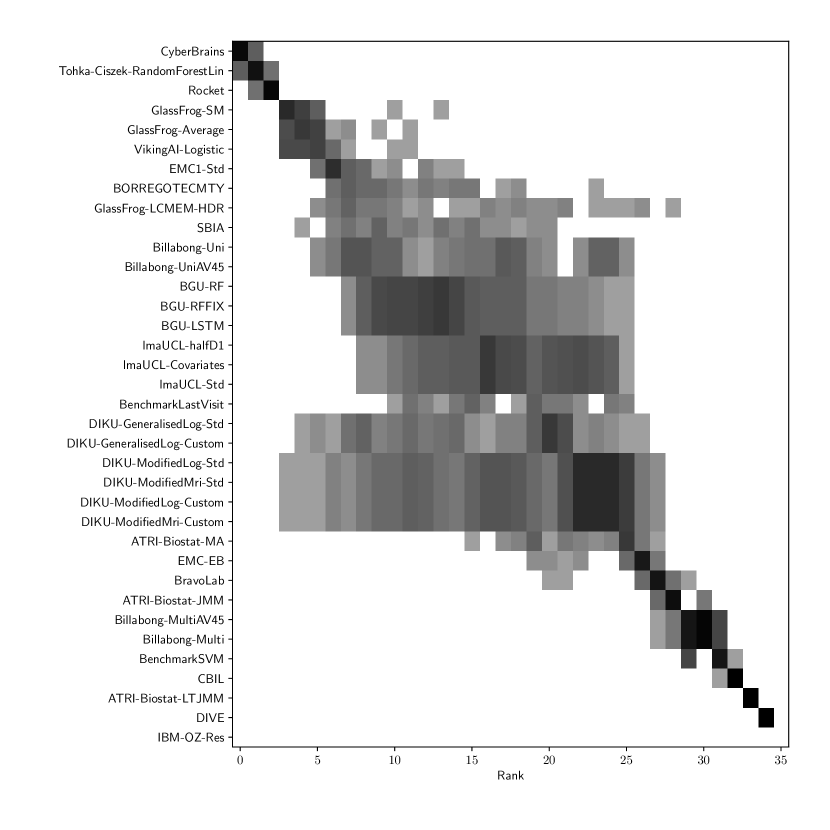

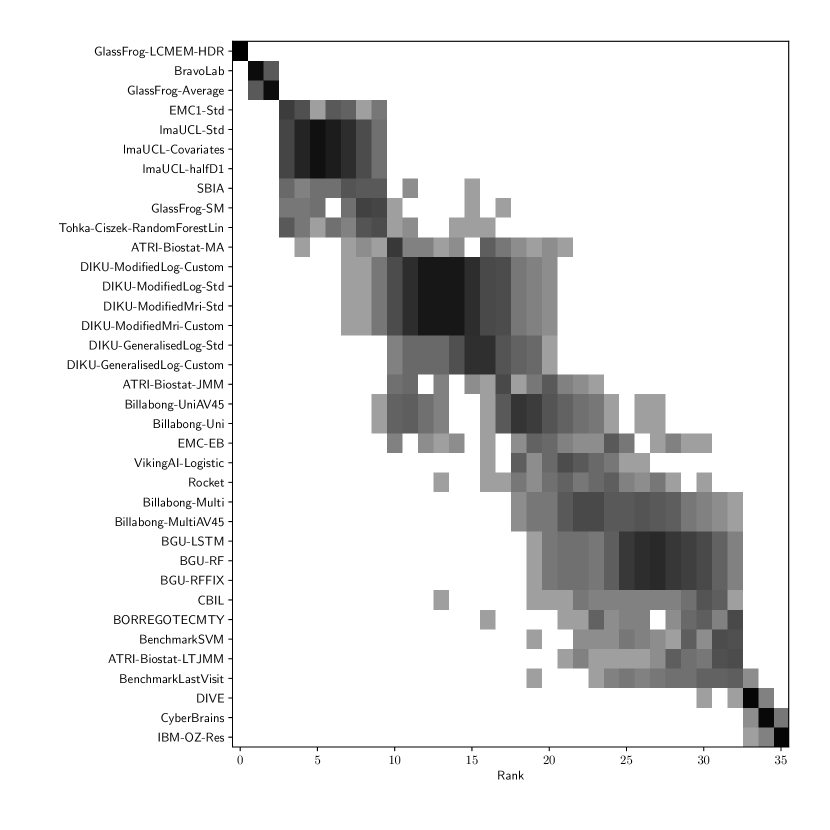

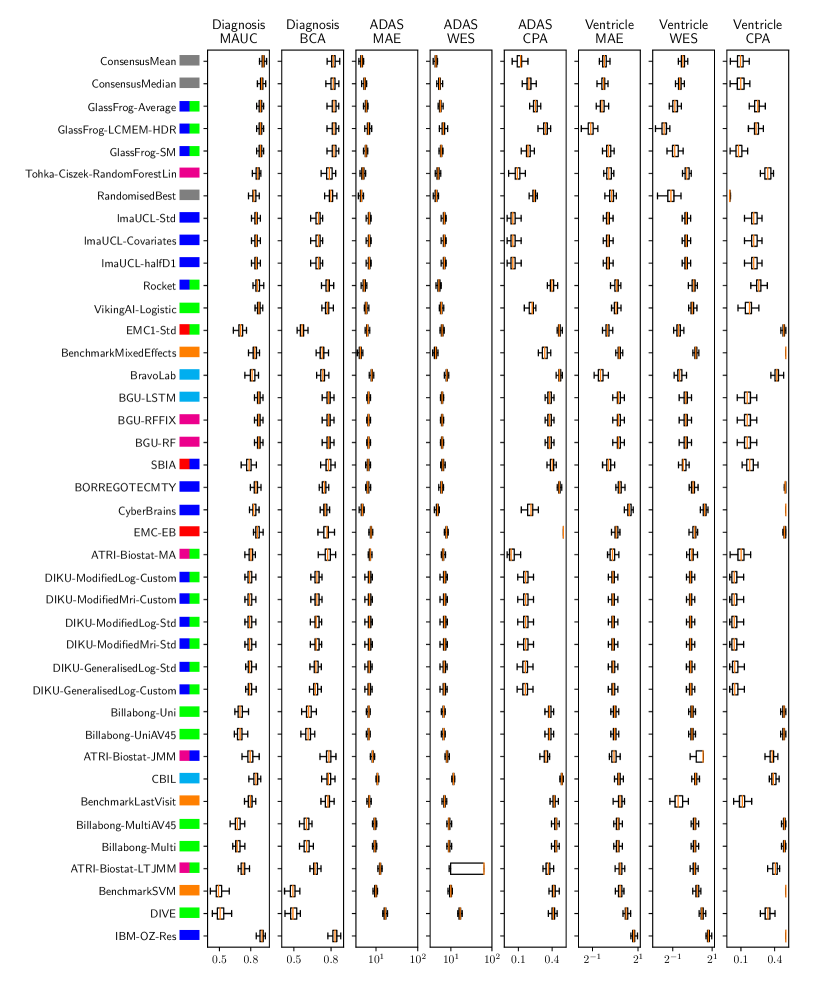

Table 3 shows the ranking of the forecasts from the cross-sectional D3 prediction set. Box-plots showing the distribution of scores, computed on 50 bootstraps of the test set, are shown in Supplementary Fig 3, while the distribution of ranks is shown in Supplementary Figs. 12 – 14. Due to the lack of longitudinal data, most submissions had lower performance compared to their equivalents from the D2 longitudinal prediction set. Among submitted forecasts, GlassFrog-Average had the best overall rank, as well as rank 2-4 on diagnosis prediction, rank 5 on ADAS-Cog13 prediction and rank 3 on ventricle prediction.

For clinical diagnosis prediction on D3, the best prediction among TADPOLE participants (team IBM-OZ-Res) scored considerably better than all benchmark methods, reducing the error of the best benchmark method by 40% for MAUC and by 25% for BCA, and achieving error rates comparable to the best predictions from the longitudinal prediction set D2. The best benchmark methods obtained a MAUC of 0.839 (BenchmarkMixedEffects) and a BCA of 0.771 (BenchmarkLastVisit). Among participant methods, IBM-OZ-Res had the best MAUC score of 0.905, significantly better than all entries other than GlassFrog-SM/-Average/-LCMEM-HDR, BGU-RF/-RFFIX/-LSTM, VikingAI-Logistic, EMC-EB, Rocket and Tohka-Ciszek-RandomForestLin according to the bootstrap hypothesis test (same methodology as in D2). This is further confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 12 by the variability of ranks under boostrap samples of the dataset, as these teams often remain at the top of the ranking. IBM-OZ-Res also had the best BCA score of 0.830 among participants. Among ensemble methods, ConsensusMean obtained the best Diagnosis MAUC of 0.917. In contrast, the best randomised prediction (RandomisedBest) obtained an MAUC of 0.811 and a BCA of 0.783. MAUC and BCA performance metrics had a relatively high correlation across all submissions (, Supplementary Fig. 5).

For Ventricle volume prediction on D3, the best prediction (GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR) scored considerably better than all benchmark methods, reducing the error of the best benchmark methods by 58% for MAE and 41% for WES, and achieving error rates comparable to the best predictions of D2. Here, the best benchmark methods had an overall Ventricle MAE of 1.13 (BenchmarkMixedEffects) and WES of 0.64 (BenchmarkLastVisit). Among participant submissions, GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR had the best MAE of 0.48, significantly lower than all other submitted entries according to the Wilcoxon signed-rank test – this is also confirmed in Supplementary Fig. 14 by the rank distribution under dataset boostraps. GlassFrog-LCMEM-HDR also had the best Ventricle WES of 0.38, while submissions by team DIKU had the best Ventricle CPA of 0.05. Among ensemble methods, ConsensusMedian obtained a Ventricle MAE of 0.71 (4th best) and WES of 0.65 (7th best). In contrast, the best randomised prediction (RandomisedBest) obtained a Ventricle MAE of 0.92, WES of 0.50 and CPA of 0. As in D2, MAE and WES scores in D3 for Ventricles had very high correlation (, Supplementary Fig. 5), while CPA showed weak correlation with MAE (, p-value = 0.17) and WES (, p-value ).

For ADAS-Cog13 on D3, the predictions submitted by participants again did not perform better than the best benchmark methods. BenchmarkMixedEffects had the best MAE of 4.23, which was significantly lower than all entries by other challenge participants. Moreover, the MAE of 4.23 was only marginally worse than the equivalent error (4.19) by the same model on D2. BenchmarkMixedEffects also had the best ADAS-Cog13 WES of 4.23, while ATRI-Biostat-MA had the best ADAS-Cog13 CPA of 0.04. Among participants’ submissions, CyberBrains ranked first in ADAS-Cog13 prediction with a MAE of 4.72, an error 11% higher than the best benchmark. Among ensemble methods, ConsensusMean obtained an ADAS-Cog13 MAE of 4.58, WES of 4.34, better than all participants’ entries. As in D2, the best randomised predictions (RandomisedBest) obtained an ADAS-Cog13 MAE of 4.54 (2nd best) and WES of 4.50 (3rd best). As in D2, MAE and WES scores for ADAS-Cog13 had high correlation ( = 0.97, Supplementary Fig. 5), while CPA showed weak, non-significant correlation with MAE ( = 0.34, p-value 0.052) or WES ( = 0.33, p-value 0.057).

Results on the custom prediction sets are presented in Supplementary Table 6.

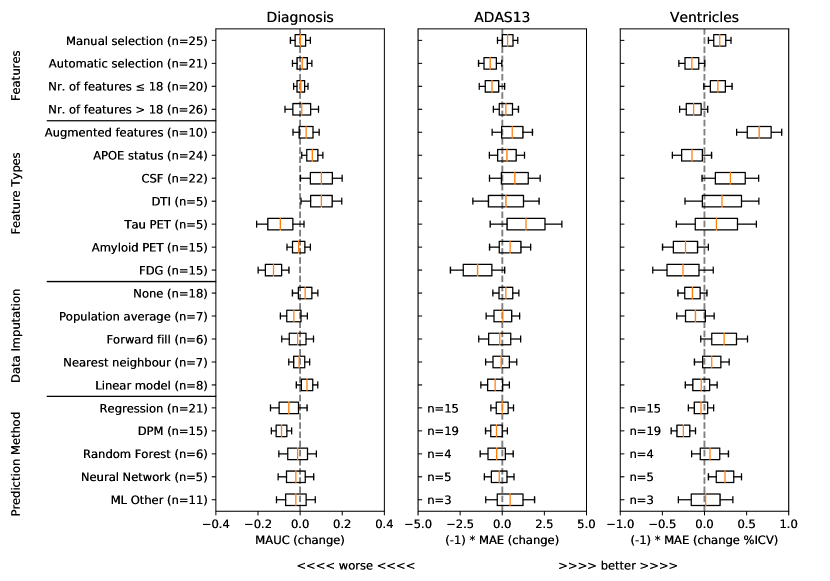

2.5 Algorithm characteristics associated with increased performance

To understand what characteristics of algorithms could have yielded higher performance, we show in Figure 1 associations from a general linear model between predictive performance and feature selection methods, different types of features, methods for data imputation, and methods for forecasting of target variables. For each type of feature/method and each target variable (clinical diagnosis, ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles), we show the distribution of estimated coefficients from a general linear model, derived from the approximated inverse Hessian matrix at the maximum likelihood estimator (see Online Methods section 5.3). From this analysis we removed outliers, defined as submissions with ADAS MAE higher than 10 and Ventricle MAE higher than 1.15 (%ICV). For all plots, distributions to the right of the gray dashed vertical line denote increased performance compared to baseline (i.e. when those characteristics are not used).

For feature selection, Figure 1 shows that methods with manual selection of features tend to be associated with better predictive performance in ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles. In terms of feature types, CSF and DTI features were generally associated with an increase in predictive performance for clinical diagnosis, while augmented features were associated with performance improvements for ventricle prediction. In terms of data imputation methods, while some differences can be observed, no clear conclusions can be drawn. In terms of prediction models, the only positive association that indicates increased performance is in the neural networks for ventricle prediction. However, given the small number of methods tested (50) and the large number of degrees of freedom, these results should be interpreted with care.

3 Discussion

In this work, we presented the results of the TADPOLE Challenge. The results of the challenge provide important insights into the current state of the field, and how well current algorithms can predict progression of AD diagnoses and markers of disease progression both from rich longitudinal data sets and, comparatively, from sparser cross-sectional data sets typical of a clinical trial scenario. The challenge further highlights the algorithms, features and data-handling strategies that tend to lead to improved forecasts. In the following sections we discuss the key conclusions that we draw from our study and highlight important limitations.

3.1 TADPOLE pushed forward performance on AD clinical diagnosis prediction

When comparing to previous state-of-the-art results in the literature, the best TADPOLE methods show similar or higher performance in AD diagnostic classification while also tackling a harder problem than most previous studies of predicting future, rather than estimating current, classification. A comparison of 15 studies presented by moradi2015machine reported lower performance (maximum AUC of 0.902 vs 0.931 obtained by the best TADPOLE method) for the simpler two-class classification problem of separating MCI-stable from MCI-converters in ADNI. A more recent method by long2017prediction reported a maximum AUC of 0.932 and accuracy of 0.88 at the same MCI-stable vs -converter classification task. However, a) TADPOLE’s discrimination of CN-converters from CN-stable subjects is harder as disease signal is weaker at such early stages, and b) the predictive performance drops in three-class problems like TADPOLE compared to two-class. Furthermore, the best out of 19 algorithms in the CADDementia Challenge bron2015standardized obtained an MAUC of 0.78.

We are unaware of previous studies forecasting future ventricle volume or ADAS-Cog13, so TADPOLE sets a new benchmark state-of-the-art performance on these important prediction tasks.

3.2 No one-size-fits-all prediction algorithm

The results on the longitudinal D2 prediction set suggest no clear winner on predicting all target variables – no single method performed well on all tasks. While Frog had the best overall submission with the lowest sum of ranks, for each performance metric individually we had different winners: Frog (clinical diagnosis MAUC of 0.931), ARAMIS-Pascal (clinical diagnosis BCA of 0.850), BenchmarkMixedEffects (ADAS-Cog13 MAE and WES of 4.19), VikingAI-Sigmoid (ADAS-Cog13 CPA of 0.02), EMC1-Std/EMC1-Custom (ventricle MAE of 0.41 and WES or 0.29), and DIKU-ModifiedMri-Std/-Custom (ventricle CPA of 0.01). Moreover, on the cross-sectional D3 prediction set, the methods by Glass-Frog had the best performance. Associations of method-type with increased performance in Fig. 1 confirm no clear increase in performance for any types of prediction methods (with the exception of neural networks for ventricle volume prediction). This raises an important future challenge to algorithm designers to develop methods able to perform well on multiple forecasting tasks and also in situations with limited data, such as D3.

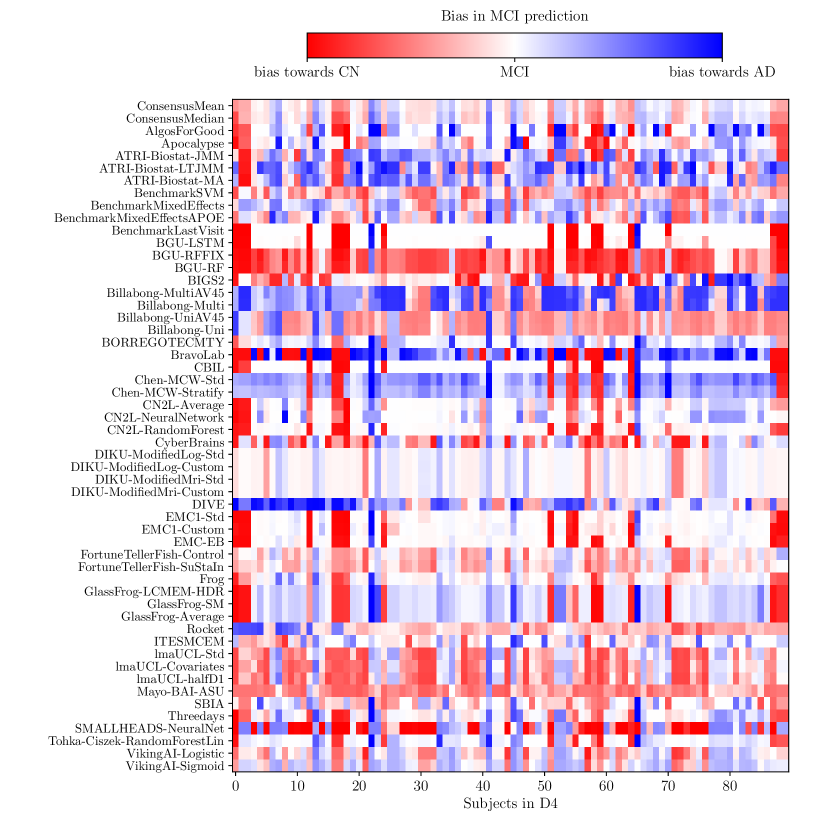

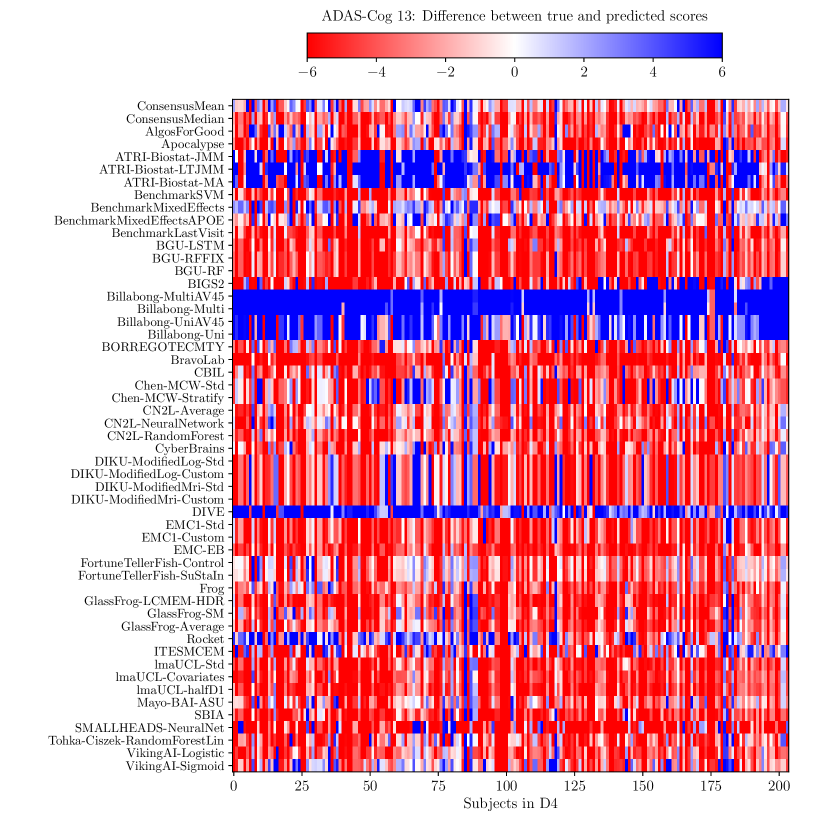

3.3 Ensemble methods perform strongly

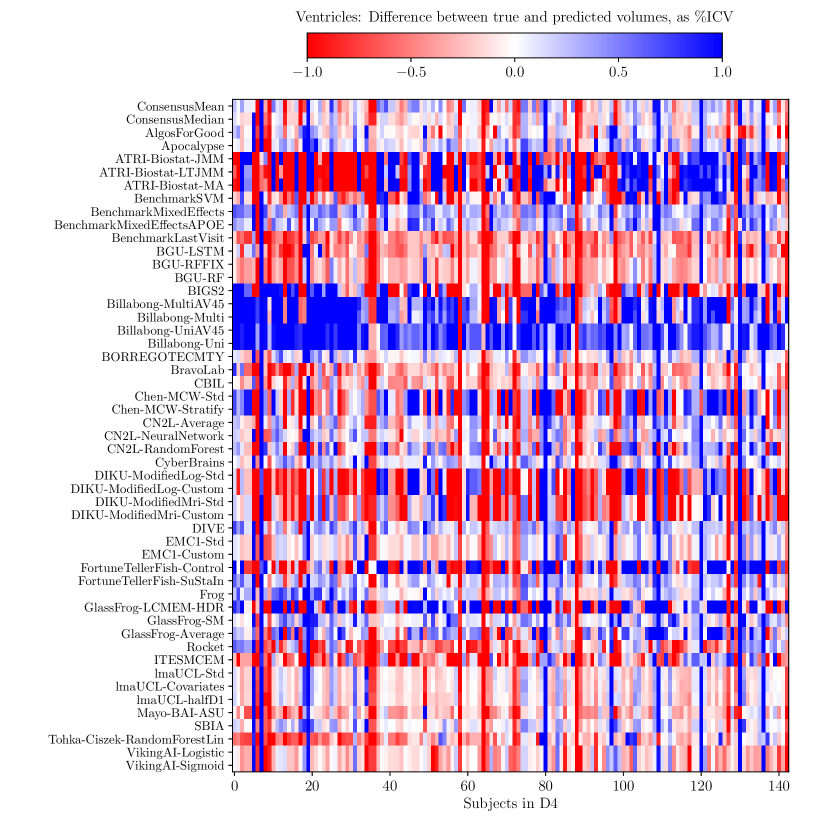

Consistently strong results from ensemble methods (ConsensusMean/ConsensusMedian outperformed all others on most tasks) might suggest that different methods over-estimate future measurements for all subjects while others under-estimate them, likely due to the underlying assumptions they make. This is confirmed by plots of the difference between true and estimated measures (Supplementary Figures 6–8), where most methods systematically under- or over-estimate in all subjects. However, even if methods were completely unbiased, averaging over all methods could also help predictions by reducing the variance in the estimated target variables.

3.4 Predictability of ADAS-Cog13 scores

ADAS-Cog13 scores were more difficult to forecast than clinical diagnosis or ventricle volume. The only single method able to forecast ADAS-Cog13 better than informed random guessing (RandomisedBest) was the BenchmarkMixedEffects, a simple mixed effects model with no covariates and age as a regressor. The difficulty could be due to variability in administering the tests or practice effects. A useful target performance level comes from the 4 points change generally used to identify responders to a drug treatment grochowalski2016examining . With the exception of the ensemble method, all submitted forecasts failed to produce mean error below 4, highlighting the substantial challenge of estimating change in ADAS-Cog13 over the 1.4 year interval – although over longer time periods, non-trivial forecasts are likely to improve in comparison to RandomisedBest, which is independent of time period. Nevertheless, for the longitudinal D2 prediction set, the MAE in ADAS-Cog13 from ConsensusMean was 3.75, which restores hope in forecasting cognitive score trajectories even over relatively short timescales.

3.5 Prediction errors from limited cross-sectional dataset mimicking clinical trials are similar to those from longitudinal dataset

For clinical diagnosis, the best performance on the limited, cross-sectional D3 prediction set was similar to the best performance on the D2 longitudinal prediction set: 0.917 vs 0.931 for MAUC (p-value = 0.14), representing a 3% error increase for D3 compared to D2. Slightly larger and significant differences were observed for ADAS MAE (3.75 vs 4.23, p-value 0.01) and Ventricle MAE (0.38 vs 0.48, p-value 0.01). It should be noted that Ventricle predictions for D3 were extremely difficult, given that only 25% of subjects to be forecasted had MRI data in D3. This suggests that, for clinical diagnosis, current forecast algorithms are reasonably robust to lack of longitudinal data and missing inputs, while for ADAS and Ventricle volume prediction, some degree of performance is lost. Future work is also required to determine the optimal balance of input data quality and quantity versus cost of acquisition.

3.6 DTI and CSF features appear informative for clinical diagnosis prediction, augmented features appear informative for ventricle prediction

DTI and CSF features are most associated with increases in clinical diagnosis forecast performance. CSF, in particular, is well established as an early marker of AD jack2010hypothetical and likely to help predictions for early-stage subjects, while DTI, measuring microstructure damage, may be informative for middle-stage subjects. On the other hand, for prediction of ventricle volume, augmented features had the highest association with increases in prediction performance. Future work is required to confirm the added value of these features and others in a more systematic way.

3.7 Challenge design and limitations

TADPOLE Challenge has several limitations that future editions of the challenge may consider addressing. One limitation is the reliability of the three target variables: clinical diagnosis, ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricle volume. First of all, clinical diagnosis has only moderate agreement with gold-standard neuropathological post-mortem diagnosis. In particular, one study beach2012accuracy has shown that a clinical diagnosis of probable AD has sensitivity between 70.9% and 87.3% and specificity between 44.3% and 70.8%. With the advent of post-mortem confirmation in ADNI, future challenges might address this by evaluating the algorithms on subjects with pathological confirmation. Similarly, ADAS-Cog13 is known to suffer from low reliability across consecutive visits grochowalski2016examining , and TADPOLE algorithms fail to forecast it reliably. However, this might be related to the short time-window (1.4 years), and more accurate predictions might be possible over longer time-windows, when there is more significant cognitive decline. Ventricle volume measurements depend on MRI scanner factors such as field strength, manufacturer and pulse sequences han2006reliability , although these effects have been removed to some extent by ADNI through data preprocessing and protocol harmonization. TADPOLE Challenge also assumes all subjects either remain stable or convert to Alzheimer’s disease, whereas in practice some of them might develop other types of neurodegenerative diseases.

For performance evaluation, we elected to use very simple yet reliable metrics as the primary performance scores: the multiclass area under the curve (mAUC) for the clinical categorical variable and the mean absolute error (MAE) for the two numerical variables. While the mAUC accounts for decision confidence, the MAE does not, which means that the confidence intervals submitted by participants do not contribute to the rankings computed in Tables 2 and 3. While the weighted error score (WES) takes confidence intervals into account, we consider it susceptible to “hacking”, e.g. participants might assign high confidence to only one or two data points and thereby skew the score to ignore most of the predictions – in practice, we did not observe this behaviour in any submission. For clinical relevance, we believe that confidence intervals are an extremely important part of such predictions and urge future studies to consider performance metrics that require and take account of participant-calculated confidence measures.

TADPOLE has other limitations related to the algorithms’ comparability and generalisability. First of all, the evaluation and training were both done on data collected by ADNI – in future work, we plan to assess how the models will generalise on different datasets. Another limitation is that we can only compare full methods submissions and not different types of features, and strategies for data imputation and prediction used within the full method. While we tried to evaluate the effect of these characteristics in Figure 1, in practice the numbers were small and hence most effects did not reach statistical significance. Moreover, the challenge format does not provide an exhaustive comparison of all combinations of data processing, predictive model, features, etc., so does not lead to firm conclusions on the best combinations but rather provides hypotheses for future testing. In future work, we plan to test inclusion of features and strategies for data imputation and prediction independently, by changing one such characteristic at a time.

Another limitation is that the number of controls and MCI converters in the D4 test set is low (9 MCI converters and 9 control converters). However, these numbers will increase over time as ADNI acquires more data, and we plan to re-run the evaluation at a later stage with the additional data acquired after April 2019. A subsequent evaluation will also enable us to evaluate the TADPOLE methods on longer time-horizons, over which the effects of putative drugs would be higher.

4 Conclusion

In this work we presented the results of the TADPOLE Challenge. The results of the challenge provide important insights into the current state of the art in AD forecasting, such as performance levels achievable with current data and technology as well as specific algorithms, features and data-handling strategies that support the best forecasts. The developments and outcomes of TADPOLE Challenge can aid refinement of cohorts and endpoint assessment for clinical trials, and can support accurate prognostic information in clinical settings. The challenge website (https://tadpole.grand-challenge.org) will stay open for submissions, which can be added to our current ranking. The open test set remains available on the ADNI LONI website and also allows individual participants to evaluate future submissions. Through TADPOLE-SHARE https://tadpole-share.github.io/, we further plan to implement many TADPOLE methods in a common framework, to be made publicly available. TADPOLE provides a standard benchmark for evaluation of future AD prediction algorithms.

5 Online Methods – Challenge design and prediction algorithms

5.1 Data

The challenge uses data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) weiner2017recent . Specifically, the TADPOLE Challenge made four key data sets available to the challenge participants:

- •

D1: The TADPOLE standard training set draws on longitudinal data from the entire ADNI history. The data set contains measurements for every individual that has provided data to ADNI in at least two separate visits (different dates) across three phases of the study: ADNI1, ADNI GO, and ADNI2.

- •

D2: The TADPOLE longitudinal prediction set contains as much available data as we could gather from the ADNI rollover individuals for whom challenge participants are asked to provide predictions. D2 includes data from all available time-points for these individuals. It defines the set of individuals for which participants are required to provide forecasts.

- •

D3: The TADPOLE cross-sectional prediction set contains a single (most recent) time point and a limited set of variables from each rollover individual in D2. Although we expect worse predictions from this data set than D2, D3 represents the information typically available when selecting a cohort for a clinical trial.

- •

D4: The TADPOLE test set contains visits from ADNI rollover subjects that occurred after 1 Jan 2018 and contain at least one of the three outcome measures: diagnostic status, ADAS-Cog13 score, or ventricle volume.

While participants were free to use any training datasets they wished, we provided the D1-D3 datasets in order to remove the need for participants to pre-process the data themselves, and also to be able to evaluate the performance of different algorithms on the same standardised datasets. Participants that used custom training data sets were asked also to submit results using the standard training data sets to enable direct performance comparison. We also included the D3 cross-sectional prediction set in order to simulate a clinical trial scenario. For information on how we created the D1-D4 datasets, see Supplementary section A. The software code used to generate the standard datasets is openly available on Github: https://github.com/noxtoby/TADPOLE.

Table 4 shows the demographic breakdown of each TADPOLE data set as well as the proportion of biomarker data available in each dataset. Many entries are missing data, especially for certain biomarkers derived from exams performed on only subsets of subjects, such as tau imaging (AV1451). D1 and D2 also included demographic data typically available in ADNI (e.g. education, marital status) as well as standard genetic markers (e.g. Alipoprotein E – APOE epsilon 4 status).

| Demographics | |||||

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | ||

| Overall number of subjects | 1667 | 896 | 896 | 219 | |

| Controls† | Number (% all subjects) | 508 (30.5%) | 369 (41.2%) | 299 (33.4%) | 94 (42.9%) |

| Visits per subject | 8.3 4.5 | 8.5 4.9 | 1.0 0.0 | 1.0 0.2 | |

| Age | 74.3 5.8 | 73.6 5.7 | 72.3 6.2 | 78.4 7.0 | |

| Gender (% male) | 48.6% | 47.2% | 43.5% | 47.9% | |

| MMSE | 29.1 1.1 | 29.0 1.2 | 28.9 1.4 | 29.1 1.1 | |

| Converters* | 18 | 9 | - | - | |

| MCI† | Number (% all subjects) | 841 (50.4%) | 458 (51.1%) | 269 (30.0%) | 90 (41.1%) |

| Visits per subject | 8.2 3.7 | 9.1 3.6 | 1.0 0.0 | 1.1 0.3 | |

| Age | 73.0 7.5 | 71.6 7.2 | 71.9 7.1 | 79.4 7.0 | |

| Gender (% male) | 59.3% | 56.3% | 58.0% | 64.4% | |

| MMSE | 27.6 1.8 | 28.0 1.7 | 27.6 2.2 | 28.1 2.1 | |

| Converters* | 117 | 37 | - | 9 | |

| AD† | Number (% all subjects) | 318 (19.1%) | 69 (7.7%) | 136 (15.2%) | 29 (13.2%) |

| Visits per subject | 4.9 1.6 | 5.2 2.6 | 1.0 0.0 | 1.1 0.3 | |

| Age | 74.8 7.7 | 75.1 8.4 | 72.8 7.1 | 82.2 7.6 | |

| Gender (% male) | 55.3% | 68.1% | 55.9% | 51.7% | |

| MMSE | 23.3 2.0 | 23.1 2.0 | 20.5 5.9 | 19.4 7.2 | |

| Converters* | - | - | - | 9 | |

| Number of clinical visits for all subjects with data available (% of total visits) | |||||

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | ||

| Cognitive | 8862 (69.9%) | 5218 (68.1%) | 753 (84.0%) | 223 (95.3%) | |

| MRI | 7884 (62.2%) | 4497 (58.7%) | 224 (25.0%) | 150 (64.1%) | |

| FDG-PET | 2119 (16.7%) | 1544 (20.2%) | - | - | |

| AV45 | 2098 (16.6%) | 1758 (23.0%) | - | - | |

| AV1451 | 89 (0.7%) | 89 (1.2%) | - | - | |

| DTI | 779 (6.1%) | 636 (8.3%) | - | - | |

| CSF | 2347 (18.5%) | 1458 (19.0%) | - | - | |

.

5.2 Forecast Evaluation

For evaluation of clinical status predictions, we used similar metrics to those that proved effective in the CADDementia challenge bron2015standardized : (i) the multiclass area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (MAUC) and (ii) the overall balanced classification accuracy (BCA). For ADAS-Cog13 and ventricle volume, we used three metrics: (i) mean absolute error (MAE), weighted error score (WES) and coverage probability accuracy (CPA). BCA and MAE focus purely on prediction accuracy ignoring confidence, MAUC and WES account for accuracy and confidence, while CPA assesses the confidence interval only. The formulas for each performance metric are summarised in Table 5. See the TADPOLE white paper marinescu2018tadpole for further rationale for choosing these performance metrics. In order to characterise the distribution of these metric scores, we compute scores based on 50 bootstraps with replacement on the test dataset.

| Formula | Definitions |

|---|---|

| where | , – number of points from class and . – the sum of the ranks of the class test points, after ranking all the class and data points in increasing likelihood of belonging to class . – number of classes. – class . |

| , , , – the number of true positives, false positives, true negatives and false negatives for class . – number of classes | |

| is the actual value in individual in future data. is the participant’s best guess at and is the number of data points | |

| , and defined as above. , where is the 50% confidence interval | |

| actual coverage probability (ACP) - the proportion of measurements that fall within the 50% confidence interval. |

5.3 Statistical Analysis of Method Attributes with Performance

To identify which features and types of algorithms enable good predictions, we annotated each TADPOLE submission with a set of 21 attributes related to (i) feature selection (manual/automatic and large vs. small number of features), (ii) feature types (e.g. “uses Amyloid PET”), (iii) strategy for data imputation (e.g. “patient-wise forward-fill”) and (iv) prediction method (e.g. “neural network”) for clinical diagnosis and ADAS/Ventricles separately. To understand which of these annotations were associated with increased performance, we applied a general linear model kiebel2007general , , where is the performance metric (e.g. diagnosis MAUC), is the nr_submissions x 21 design matrix of binary annotations, and show the contributions of each of the 21 attributes towards achieving the performance measure .

5.4 Prediction Algorithms

Team: AlgosForGood (Members: Tina Toni, Marcin Salaterski, Veronika Lunina, Institution: N/A)

Feature selection: Manual + Automatic: Manual selection of uncorrelated variables from correlation matrix and automatic selection of variables that have highest cumulative hazard rates in survival regression from MCI to AD.

Selected features: Demographics (age, education, gender, race, marital status), cognitive tests (ADAS-Cog13, RAVLT immediate, RAVLT forgetting, CDRSOB, ADAS11, FDG), Ventricles, AV45, ICV, APOE4.

Missing data: Fill-in using last available value from corresponding patient

Confounder correction: none

Method category: Statistical Regression / Proportional hazards model

Prediction method:

- •

Diagnosis: Aalen additive regression constructing a cumulative hazard rate for progressing to AD.

- •

ADAS-Cog13: regression using change in ventricles/ICV as predictive variable, stratified by last known diagnosis.

- •

Ventricles: regression over month, with several pre-processing steps: 1. Enforced monotonicity by accumulating maximum value, 2. For APOE positive patients used only last three visits due to non-linearity 3. Stratified by diagnosis

Team: Apocalypse (Members: Manon Ansart, Stanley Durrleman, Institution: Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle épinière, ICM, Paris, France)

Feature selection: Manual – important features were identified by looking at the correlations with the diagnosis. Personal knowledge of the disease was also used to complement those results and select relevant features. Different feature sets were compared using cross-validation.

Selected features: Cognitive features (ADAS-Cog13, MMSE, RAVLT immediate, FAQ, CDRSOB), MRI features (WholeBrain, Entorhinal, Fusiform, MidTemp, Ventricles, Entorhinal, Hippocampus), APOE4, education, age, clinical diagnosis

Missing data: Filled in using the mean feature value

Confounder correction: none

Method category: Machine learning / Regression

Prediction method: Linear regression is used to first predict the future of a set of features (MMSE, ADAS-Cog13, CDRSOB, RAVLT, Ventricles) at the prediction dates. Afterwards, an SVM is used to predict the current diagnosis for each prediction date, based on the forecasted features as well as other features which are constant for the subject (APOE4, education, age at last known visit).

Team: ARAMIS-Pascal (Members: Pascal Lu, Institution: Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle épinière, ICM, Paris, France)

Feature selection: Manual, based on known biomarkers from the literature.

Selected features: APOE4, cognitive tests (CDRSB, ADAS11, ADAS-Cog13, MMSE, RAVLT immediate, FAQ), volumetric MRI (hippocampus, ventricles, whole brain, entorhinal, fusiform, middle temporal, ICV), whole brain FDG, CSF biomarkers (amyloid-beta, tau, phosphorylated tau), education and age.

Missing data: Imputed using the average biomarker values across the population.

Confounder correction: none

Method category: Statistical Regression / Proportional hazards model

Prediction method: For diagnosis prediction, the Aalen model for survival analysis was used to predict the conversion from MCI to AD, which returns the probability of a subject remaining MCI as a function of time. The method assumes cognitively normal and dementia subjects will not convert and thus will remain constant. The method did not predict ADAS-Cog13 or Ventricles.

Publication link: https://hal.inria.fr/tel-02433613/document

Team: ATRI_Biostat (Members: Samuel Iddi1,2, Dan Li1, Wesley K. Thompson3 and Michael C. Donohue1. Institutions: 1Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute, USC, USA; 2Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Ghana, Ghana; 3Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, University of California, USA)

Feature selection: Automatic - features were ranked by their importance in classifying diagnostic status using a random forest algorithm. All cognitive tests, imaging biomarkers, demographic information and APOE status were considered as potential features

Selected features: ADAS-Cog13, EcogTotal, CDRSOB, FAQ, MOCA, MMSE, RAVLT immediate, Ventricles/ICV, Entorhinal, Hippocampus/ICV and FDG Pet. Age, gender and APOE status were included as covariates. The interaction between diagnosis at first available visit and years since first visit was also considered.

Missing data: Imputed using the MissForest Algorithm, based on a non-parametric random forest methodology stekhoven2011missforest . The algorithm was chosen based on its ability to handle mixed-type outcomes, complex interactions and non-linear relationships between variables.

Confounder correction: APOE status, last known clinical status, age and gender.

Method category: Machine learning and data-driven disease progression models

Prediction method: The method applied different types of mixed-effects models to forecast ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles, and then used a Random Forest classifier to predict the clinical diagnosis from the forecasted continuous scores.

- •

JMM – Joint Mixed-effect Modelling with subject-specific intercept and slope.

- •

LTJMM – Latent Time Joint Mixed-effect Modelling with subject-specific intercept, slope and time-shift

- •

MA – Model average of the two models above, as well as a third model where random intercepts are shared across outcomes.

Confidence Intervals: The 50% prediction intervals for ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles were obtained by taking the 25th and 75th percentile of the posterior predicted samples.

Publication link: https://braininformatics.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40708-019-0099-0

Team: BGU (Members: Aviv Nahon, Yarden Levy, Dan Halbersberg, Mariya Cohen, Institution: Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beersheba, Israel)

Feature selection: Automatic – used the following algorithm: 1. Find the two variables with highest correlation (Spearman for continuous variables and Mutual information for discrete variables). 2. Compute the correlation of each variable with the target variables separately and remove the variable with the lower correlation. 3. If there are still pairs of variables with a correlation of more than 80%, repeat from step 1.

Selected features: Cognitive tests (CDRSOB, MMSE, RAVLT, MOCA, all Ecog), MRI biomarkers (Freesurfer cross-sectional and longitudinal), FDG- PET (hypometabolic convergence index), AV45 PET (Ventricles, Corpus Callosum, Hippocampus), White-matter hypointensities’ volume, CSF biomarkers (amyloid-beta, tau, phosphorylated tau). For each continuous variable, an additional set of 20 augmented features was used, representing changes and trends in variables (e.g. mean, standard deviation, trend mean, trend standard deviation, minimum, mean minus global mean, baseline value, last observed value). This resulted in 233 features, which were used for prediction.

Missing data: Random forest can deal automatically with missing data. LSTM network used indicator that was set to zero for missing data.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Machine learning

Prediction method:

- •

BGU-LSTM : This model consisted of two integrated neural networks: an LSTM network for modelling continuous variables and a feed-forward neural network for the static variables.

- •

BGU-RF : A semi-temporal Random Forest was used which contained the augmented features.

- •

BGU-RFFIX : Same as BGU-RF, but with small correction for the prediction of diagnosis: whenever the model predicted AD with probability higher than 80%, the probability of CN was changed to zero and vice versa.

Team: BIGS2 (Members: Huiling Liao, Tengfei Li, Kaixian Yu, Hongtu Zhu, Yue Wang, Binxin Zhao, Institution: University of Texas, Houston, USA)

Feature selection: Automatic – used auto-encoder to extract aggregated features.

Selected features: All continuous features in D1/D2, which represented the input for the autoencoder. Apart from the autoencoder-extracted features, other features used for the classifier were demographic information, APOE status, whole brain biomarkers from MRI (volume) and PET (FDG, PIB and AV45), and MMSE.

Missing data: SoftImpute method mazumder2010spectral was used for imputing missing data. The complete dataset was then used as input to the autoencoder.

Confounder correction: none

Method category: Regression and Machine Learning

Prediction method: Linear models were used to predict ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricle scores independently. For prediction of clinical diagnosis, a random forest was used based on the autoencoder-extracted features and the other selected features.

Team: Billabong (Members: Neil Oxtoby, Institution: University College London, UK)

Feature selection: Manual, using knowledge from literature

Selected features: MRI biomarkers normalised by ICV (ventricles, hippocampus, whole brain, entorhinal, fusiform, middle temporal), FDG, AV45, CSF biomarkers (amyloid beta, tau, phosphorylated tau) and cognitive tests (ADAS-Cog13, MMSE, MOCA, RAVLT immediate). Separate submissions (Billabong-UniAV45, Billabong-MultiAV45) were made which also included AV45, that was initially excluded due to noise.

Missing data: Only imputed during staging via linear regression against age. The method can deal with missing data during training.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Data-driven disease progression model

Prediction method: For each selected feature independently, a data-driven longitudinal trajectory was estimated using a differential equation model based on Gaussian Process Regression oxtoby2018data . Subjects were staged using either a multivariate or univariate approach:

- •

Billabong-Uni: Univariate staging which estimates disease stage for each target variable independently.

- •

Billabong-Multi: Multivariate staging that combines all selected features, producing an average disease stage.

For the prediction of clinical diagnosis, the historical ADNI diagnoses were mapped to a linear scale using partially-overlapping squared-exponential distribution functions. The linear scale and the three distributions were used to forecast the future diagnoses.

Custom prediction set: Predictions were made also for a custom dataset, which was similar to D3 but missing data was filled in using the last available biomarker data.

Confidence Intervals: The 25th and 75th percentiles of the GPR posterior were each integrated into a trajectory to obtain 50% confidence (credible) intervals for the forecasts of ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles/ICV.

Publication link: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy050

Team: BORREGOSTECMTY (Members: José Gerardo Tamez-Peña, Institution: Tecnologico de Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico)

Feature selection: Automatic, using bootstrapped stage-wise selection.

Selected features: Main cognitive tests (excluding subtypes), MRI biomarkers, APOE status, demographic information (age, gender, education) and diagnosis status. Augmented features were further constructed from the MRI set: the cubic root of all volumes, the square root of all surface areas, the compactness, the coefficient of variation, as well as the mean value and absolute difference between the left and right measurements.

Missing data: Imputed using nearest-neighbourhood strategy based on L1 norm.

Confounder correction: Gender and intracranial volume (ICV) adjustments relative to controls.

Method category: Regression (ensemble of statistical models)

Prediction method: ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles were predicted using an ensemble of 50 linear regression models, one set for each diagnostic category. The best models were selected using Bootstrap Stage-Wise Model Selection, using statistical fitness pencina2008evaluating tests to evaluate models and features to use within the models. All selected models were then averaged in a final prediction using bagging. For prediction, the last known diagnosis of the subject was used to select the category of models for forecasting.

For the prediction of clinical diagnosis, a two-stage approach was used based on prognosis and time-to-event estimation. The prognosis approach used an ensemble of 50 regression models to estimate the future diagnosis, while the time-to-event method used an ensemble of 25 models to estimate the square root of the time it took for a subject to convert to MCI or AD. These approaches were performed independently for CN-to-MCI, MCI-to-AD and CN-to-AD conversion.

Confidence Intervals: The 50% confidence intervals for ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricle volume were estimated by extracting the interquartile range of the 50 regression estimates.

Repository link: https://github.com/joseTamezPena/TADPOLE

Team: BravoLab (Members: Aya Ismail, Timothy Wood, Hector Corrada Bravo, Institution: University of Maryland, USA)

Feature selection: Automatic, using a random forest to select features with highest cross-entropy or GINI impurity reduction.

Selected features:

- •

Ventricle prediction: MRI volumes of ventricular sub-regions (Freesurfer cross-sectional and longitudinal)

- •

ADAS-Cog13 prediction: RAVLT, Diagnosis, MMSE, CDRSOB

- •

Diagnosis prediction: ADAS-Cog13, ADAS11, MMSE, CSRSOB

Missing data: Imputation using Hot Deck andridge2010review was done only for data missing at random.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Machine learning

Prediction method: A long-short term memory network (LSTM) with target replication was trained independently for each category: Diagnosis, ADA13 and Ventricles. All existing data was used for the first forecast, after which the output of the last prediction was used as input for the next prediction, along with other features that remain constant over time. Since subjects had a different number of visits and available biomarker data, the network was adapted to accept inputs of variable length. For predictions, the network used a weighted mean absolute error as a loss function. In addition, for the prediction of the clinical diagnosis, a soft-max function was used to get the final prediction.

Team: CBIL (Members: Minh Nguyen, Nanbo Sun, Jiashi Feng, Thomas Yeo, Institution: National University of Singapore, Singapore)

Feature selection: Manual, based on model performance on D1 subset.

Selected features: Cognitive tests (CDRSOB, ADAS11, ADAS-Cog13, MMSE, RAVLT immediate, learning, forgetting and percent forgetting, MOCA, FAQ), MRI biomarkers (entorhinal, fusiform, hippocampus, ICV, middle temporal, ventricles, whole brain), whole brain AV45 and FDG, CSF biomarkers (amyloid-beta, tau, phosphorylated tau).

Missing data: Imputation using interpolation.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Machine learning and data-driven disease progression model

Prediction method: Recurrent neural network adapted for variable duration between time-points. A special loss function was designed, which ensured forecasts at timepoints close together are more correlated than those at timepoints further apart.

Confidence Intervals: hardcoded values

Publication link: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/755058v1

Repository link: https://github.com/ThomasYeoLab/CBIG/tree/master/stable_projects/predict_phenotypes/Nguyen2020_RNNAD

Team: Chen-MCW (Members: Gang Chen, Institution: Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA)

Feature selection: Manual

Selected features: ADAS-Cog13, MMSE, MRI volumes (hippocampus, whole brain, entorhinal, fusiform and middle temporal), APOE status, gender and education.

Missing data: No imputation performed.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Regression and data-driven disease progression model

Prediction method: Prediction of ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles was made using linear regression using age, APOE status, gender and education as covariates. Different models were estimated for CN, MCI and AD subjects. For diagnosis prediction, an AD risk stage was calculated based on the Event-based probability (EBP) model chen2016staging . Prediction of clinical diagnosis was then made based on two approaches:

- •

Chen-MCW-Std: Predict diagnosis based on AD stage as well as APOE4, gender and education using a Cox proportional hazards model.

- •

Chen-MCW-Stratify: As above, but the model was further stratified based on AD risk stages, into low risk and high-risk.

Team: CN2L (Members: Ke Qi1, Shiyang Chen1,2, Deqiang Qiu1,2, Institutions: 1Emory University, 2Georgia Institute of Technology)

Feature selection: Automatic

Selected features: For the neural network, all features in D1/D2 are used; For the random forest, the main cognitive tests, MRI biomarkers (cross-sectional only), FDG, AV45, AV1451, DTI, CSF, APOE, demographics and clinical diagnosis are used.

Missing data: Imputation in a forward filled manner (i.e. using last available value).

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Machine learning

Prediction method:

- •

CN2L-NeuralNetwork : 3-layer recurrent neural network, 1024 units/layer. Dropout layers (dropout rate:0.1) were added to output and state connections to prevent overfitting. Adam method was used for training. Validation was performed using a leave-last-time-point-out approach.

- •

CN2L-RandomForest : Random forest method was used, where features of small importance for diagnosis prediction were filtered out. For the prediction of clinical diagnosis, an ensemble of 200 trees was trained on a class-balanced bootstrap sample of the training set. For the prediction of ADAS-Cog13 and Ventricles, an ensemble of 100 trees was used. Different predictions are made for different previous visits of a patient, and the final prediction is taken as the average of all predictions.

- •

CN2L-Average : The average of the above two methods.

Confidence Intervals: Confidence intervals are estimated based on probabilities output of the model.

Publication link: https://cds.ismrm.org/protected/18MPresentations/abstracts/3668.html Chen et al., ISMRM, 2018 chen2018is

Team: CyberBrains (Members: Ionut Buciuman, Alex Kelner, Raluca Pop, Denisa Rimocea, Kruk Zsolt, Institution: Vasile Lucaciu College, Baia Mare, Romania)

Feature selection: Manual

Selected features: MRI volumes (Ventricles, middle temporal), ADAS-Cog13, APOE status

Missing data: For subjects with no ventricle measurements, authors computed an average value based on ADAS-Cog13 tests. This was used especially for D3 predictions.

Confounder correction: None

Method category: Regression